Scripture

Mark 4:26-34

He also said, ‘The kingdom of God is as if someone would scatter seed on the ground, and would sleep and rise night and day, and the seed would sprout and grow, he does not know how. The earth produces of itself, first the stalk, then the head, then the full grain in the head. But when the grain is ripe, at once he goes in with his sickle, because the harvest has come.’

He also said, ‘With what can we compare the kingdom of God, or what parable will we use for it? It is like a mustard seed, which, when sown upon the ground, is the smallest of all the seeds on earth; yet when it is sown it grows up and becomes the greatest of all shrubs, and puts forth large branches, so that the birds of the air can make nests in its shade.’

With many such parables he spoke the word to them, as they were able to hear it; he did not speak to them except in parables, but he explained everything in private to his disciples.

You have heard the ancient story.

Let us listen now for the word of God.

Responsive Call to Worship (loosely based on Psalm 92)

For Contemplation as Part of Worship

It is a good and healthy thing

to wake up to a new day with gratitude—

with thoughts and words of praise—

both about what’s been and what’s anticipated—

all within intentionally more specific gratitude

for the blessing—the gift—the wonder

of Your steadfast love, our God—

the faithfulness, in the assurance of which, we rest.

And as it is good to thus wake up,

so too, to lie down at night

listing—naming—maybe chanting—

identifying specific blessings

to the sound of imagined musical accompaniment—

the organ maybe—or not,

a full orchestra,

power chords on an electric guitar,

a jazz quartet.

It matters not.

The gift of music offered in response to the gift of grace.

For day by day and through my nights,

the signs of Your work sing to me—

signify Your presence and bring me joy.

How great the effects I know to name of faithful love.

How transformative their consequence—

how profound—pervasive—extensive.

Yet there are many who do not—

will not—cannot see—

would never dream,

amidst all the wickedness of our world—

within the reality that jerks and cheats flourish and prosper

in culturally approved and measurable ways—

there are many who do not know

the wicked, whatever appearance to the contrary,

have already been doomed in, by, and through love.

I guess some of those are blinded

by superficiality and selfishness.

Then there are those,

I’m not sure why they don’t—won’t name You.

Righteousness and justice

grow from Your heart, our God,

strong and true, green and healthy, into the light,

producing their bountiful fruit in the world—

another sign of who You are,

my solid, reliable foundation,

my rock

in whom there is but good—

in whom there is but love.

And again, I name my blessing.

Sermon

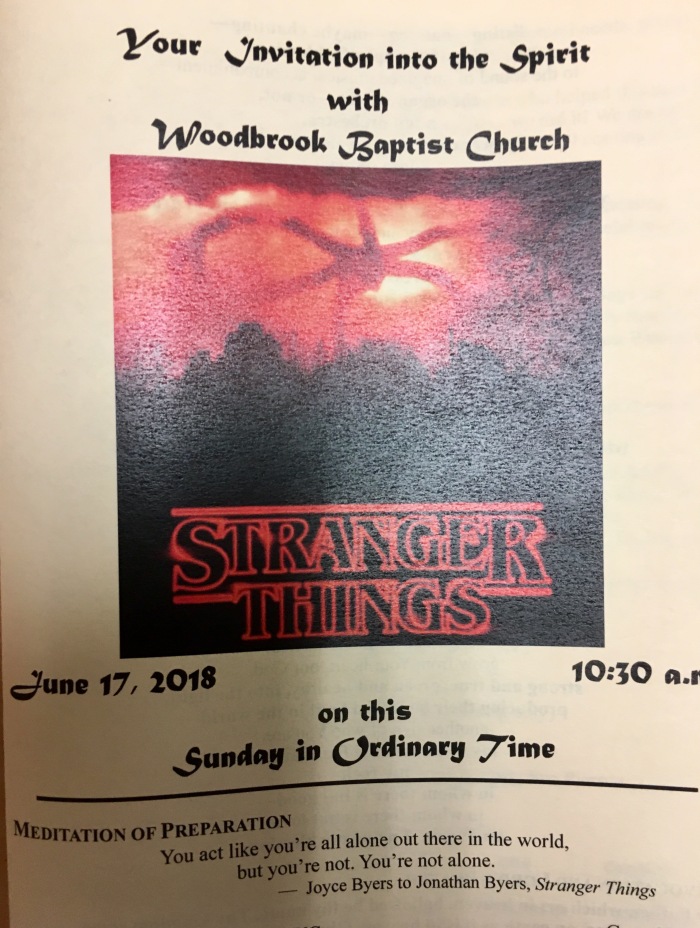

So maybe you remember we mentioned,

or if you’re watching/have watched the Netflix TV series Stranger Things,

maybe you saw the episode

in which El opened that inter-dimensional door

letting in the monster?

Those in charge at Hawkins lab hoped to harness

and exploit its power.

Because that’s what they did there at Hawkins Lab.

They exploited power.

Because some ends supposedly justified whatever means.

Then when they discovered the monster could not be controlled,

they sought to contain it on the bottom floor of the lab.

But what we come to find out, along with them,

is that evil can’t be contained.

Evil finds ways to spread,

and the separation of one evil from another

does not exist.

Distinctions between evil are always illusory—

as much as the folks at Hawkins Lab try and justify what they do

as what needs to be done to keep us safe

as being strong enough to do what needs be done—

as much as we always explain away our evil

in comparison to theirs.

As if we can isolate evil always outside ourselves.

Blaming parents for risking life and limb

wanting a better future for their children is evil—

especially given how integral it is to our foundational myths

of the brave families who risked life and limb

for a better future across the ocean in a new land—

and then ever further west in that new land.

I’m not saying there aren’t legitimate concerns.

I’m not denying the complexity of the challenge of circumstances.

I am saying, blaming parents,

and separating children from their parents,

as a deterrent, as part of a zero tolerance mindset, is evil.

Justifying it in the name of God is blasphemy.

And blaming others for how you have chosen to act is loathsome.

That has to be named.

For as much as that is who we are,

it is not who I understand God calling us to be.

And that is a message coming clearly in one voice

from churches at their most conservative to the most liberal.

Evil finds ways to spread,

and the separation of one evil from another

does not exist.

Distinctions between evil are always illusory.

Of course, the same is true for good.

Both observations corollaries to my hypothesis

that the means are the ends.

Jesus also said on the shores of the sea of Galilee,

“The kingdom of God is as if someone

would scatter seed on the ground,

and would sleep and rise night and day,

and the seed would sprout and grow, he does not know how.

The earth produces of itself, first the stalk, then the head,

then the full grain in the head.

But when the grain is ripe,

at once he goes in with his sickle,

because the harvest has come.”

Here we have the kingdom of God compared not to something,

but to a story—an unfolding—a happening.

And right off the bat,

there are two profoundly different ways of reading this parable.

Is it God who sows the seed?

It’s pretty clear in the first parable Jesus tells the crowds by the lake

(the parable of the sower) that God is the actor,

the initiator, creator, redeemer,

and that the seed that takes root in us.

So is it God who sows in our parable too,

and having taken that initiative in creation and blessing,

waits to see what we do—

what fruit we produce before returning for the harvest?

Or, are we the sowers of seed—

taking initiative to share with others

what we have found to be most significant

most profound and most transformative in our own experience,

and then trusting the mysterious work of the divine

to effect growth and change we cannot see or control

until one day, maybe, we see the fruit.

And what if it’s my favorite answer to either/or questions?

What if it’s both?

What if we can claim the double assurance

of trusting both God’s mysterious work

and trusting God as alpha and omega—

beginning and end?

Which means we then also accept the double challenge

of being the ones who are to both initiate and share with others

and encourage and facilitate growth—

in us as in others.

However we read it,

we find the kingdom of God is a partnership

with both God and us having different responsibilities

and with both God and us waiting and trusting the other.

There’s what we initiate and what happens in consequence,

and there’s what God initiates and what happens in consequence.

And if we accept the parable at its most complex,

then there’s no way we can read it as a prescriptive

here’s-what-we’re-responsible-for-here’s-what-God-does,

but only through a blurring of the lines and responsibilities.

We are together responsible, and we wait together,

trusting the mystery of the process—of the story still unfolding.

The Greek word translated “of itself”—the earth produces “of itself”—

is actually the one from which we get our word “automatic.”

When we’re working with God and taking responsibility and trusting the process,

there is an automatic unfolding of God’s story in growth and transformation.

Now that’s true for evil too, by the way.

There are initiatives not of God,

and by those not following God (whether they’ll admit that or not),

and what automatically keeps unfolding from such actions.

The kingdom of God unfolds from God.

The ways of the world unfold too, when they are chosen.

The means are the ends,

and what is our harvest?

He also said, “With what can we compare the kingdom of God,

or what parable will we use for it?

It is like a mustard seed, which, when sown upon the ground,

is the smallest of all the seeds on earth;

yet when it is sown it grows up

and becomes the greatest of all shrubs,

and puts forth large branches,

so that the birds of the air can make nests in its shade.”

Traditionally, we tend to focus—

I’m fairly confident most of you will have heard a sermon or two,

on the itty-bitty seed

(and to be fair, the mustard seed is explicitly identified in the parable

as the smallest of all the seeds on earth.

It’s not that that’s wrong—that those sermons are wrong.

I think Clark has brought in mustard seeds before.

They are tiny)—

the itty-bitty seed that becomes a great, big, tall, majestic, magnificent—

shrub.

Matthew and Luke change the story—

change the story … and botanical definitions.

Matthew writes when it has grown, it is the greatest of shrubs

and becomes a tree (Matthew 13:32), while Luke writes

it grew and became a tree (Luke 13:19)

which makes it a whole other story of transformation!

It is just a shrub—

achieving a maximum height of anywhere from two to ten feet!

I mean, relatively speaking, if you’re emphasizing small to big

a tiny seed (1 to 2 millimeters in diameter) that becomes a shrub—

even a big shrub as shrubs go,

is still not as impressive as a bigger seed—say an inch and a half or so,

that comes a cedar of Lebanon which can grow up to 120/130 feet—

with a spread of almost 100 feet and a trunk

that can exceed 8 feet in diameter!

There’s even a prophetic tradition identifying the great cedars

not only with Judah and Israel, but also the great kingdoms of earth:

Egypt, Babylon, and Assyria.

So the emphasis here is on small—

so small it’s almost pejorative—

(if you had faith the size of a mustard seed

[Matthew 17:20; Luke 17:6]).

And so, growing in the shadow of the Roman Empire,

a delightfully subversive affirmation to encourage the church:

“the mustard bush, whether domesticated in a garden or wild in a field,

was an extremely noxious and dangerous plant,

as it threatened to take over whatever area its seed finally took root in.

Pliny the Elder says of it, ‘Mustard … with its pungent taste

and fiery effect … grows entirely wild,

though it is improved by being transplanted:

but on the other hand when it has once been sown

it is scarcely possible to get the place free of it,

as the seed when it falls germinates at once’ (Natural History, 19.170-1)”

(Ben Witherington III, The Gospel of Mark

[Grand Rapids: Wm.B.Eerdmans, 2001] 172).

“It is hard to escape the conclusion that Jesus deliberately

likens the rule of God to a weed” (quoted in Witherington, 172).

So there’s that.

More than small to big and impressive,

it’s small to hardy and resistant and pervasive—

invasive,

and great is the faithfulness of God.

Or, what’s great is not the shrub,

not whatever’s impressive about it

or scrappy or hardy, pervasive—nothing about the shrub,

but about what the shrub offers.

And the whole point, do you see?—

the whole point is not that it’s itty-bitty

and then gets big or impressive or takes over,

it’s so that—the whole thing is so that—

the whole process is so that the seed becomes a shrub

that becomes a home.

It meets the needs of a community—

so that the birds of the air can make nests.

And there is a sense, reading this,

of the birds of the air in a cumulative sense—

as an expansive image of a multitude of birds.

Maybe the reference to birds of the air reminds you

as it did me, of the creation stories.

On the fifth day, God created the birds of the air

and on the sixth day, after creating humankind,

made them stewards of creation—including the birds of the air

(Genesis 1:20, 26, 30; 2: 19, 20).

But again, if you were going for room for more birds,

surely a cedar of Lebanon would provide more shade and shelter

instead of trying to imagine the birds of the air

nesting in a shrub that’s barely 10 feet high!

Unless of course, maybe—

even more subtly—more creatively—so wise—

unless the affirmation

is that this unimpressive shrub is bigger that it looks—

like a certain stable in Narnia.

Y’all familiar with the C.S. Lewis book The Last Battle?

Tirian had thought – or he would have thought if he had had time to think at all – that they were inside a little thatched stable, about twelve feet long and six feet wide. In reality they stood on grass, the deep blue sky was overhead, and the air which blew gently on their faces was that of a day in early summer. …

“The door?” said Tirian.

“Yes,” said Peter. “The door you came in – or came out – by. Have you forgotten?” … Tirian looked and saw the queerest and most ridiculous thing you can imagine. Only a few yards away, clear to be seen in the sunlight, there stood up a rough wooden door and, round it, the framework of the doorway: nothing else, no walls, no roof. He walked towards it, bewildered … He walked round to the other side of the door. But it looked just the same from the other side….

“Fair Sir,” said Tirian to the High King, “this is a great marvel.” … “It seems, then … that the Stable seen from within and the Stable seen from without are two different places.”

“Yes,” said the Lord Digory. “Its inside is bigger than its outside.”

“Yes,” said Queen Lucy. “In our world too, a Stable once had something inside it that was bigger than our whole world”

(C.S. Lewis, The Last Battle [New York: HarperCollins, 1965] 156-161).

In the less than impressive,

in what does not measure up to the kingdoms of the world

by the standards of the world,

there is nonetheless room for all.

And this kingdom does not worry about immigrants,

it welcomes them—celebrates them—

as the Bible says to do!

This kingdom does not exclude—does not turn away.

It is a kingdom invested in justice—for all—

in community.

It’s a fake kingdom, of course, by the standards of the world,

but more real than any other.

How’s that for faithful?

Notice in both our parables the shift from the individual—

from the seed and the shrub to the birds nesting in it—

from individual seeds to a crop and a harvest—

that which will provide for a community.

There’s a “so that” there too, isn’t there?

The unfolding of grace into community so that

the community can be nurtured and nourished on good fruit.

Movement from the individual to the communal,

surely there’s something of the kingdom of God to that!

I mentioned last week,

the movement in Stranger Things

from some who risk so much on behalf of others

to more and more who do so.

To the point, that it begins to feel uncomfortable

when individuals are left out—

when they’re excluded.

For those of you who watch or have watched

I’m thinking of Lucas and Mike.

I’m thinking of Max.

Barbara, early on. There’s tension—disagreement,

and they’re on the outside, and it doesn’t feel right.

Our culture is set up in so many ways

to evaluate people individually.

To assess individual success and accomplishment.

There’s a corresponding valuation of individual responsibility.

That’s not all bad.

Lot of good to that.

But it’s not all good.

If it were our culture telling these stories instead of Jesus,

the first parable would be about growing a harvest

and getting as much money for it as possible.

The goal is not the nourishment of community

but the profit of the individual or the corporation.

Fair?

The second parable would be about growing a bush

and then putting a fence around it

so no one can nest in it without paying rent—their fair share.

After all, who wants to deal with all that noise and the bird poop, right?

A parable—a parable by Jesus,

invites us to consider how we would tell the parable—

in our homes, in our churches, in our country,

and to reflect on how those tellings differ

from the stories as Jesus told them—

to reflect on what that says about us—

our families, our churches, our country.

Because our stories honestly

do not consistently reflect the kingdom of God.

They tend to (with some wonderful exceptions)

reflect an us-or-them mentality

that’s part of a zero sum game

creating winners and losers.

So Mark adds a concluding word about parables.

With many such parables he spoke the word to them,

as they were able to hear it

(because they’re not the stories they would have told

anymore than they’re the stories we would tell);

he did not speak to them except in parables,

but he explained everything in private to his disciples.

This sequence of stories starts

with Jesus talking to a large crowd by the sea (Mark 4:1).

Then you have this very odd verse:

When he was alone, those who were around him—

so he wasn’t alone, right?!

those who were around him—along with the twelve

(what does alone mean to Mark?)

all those people who were alone with him

asked him about the parables (Mark 4:10).

Because arables are not crystal clear.

They’re not meant to be.

They’re not definitions or explanations.

Jesus went on to say: “To you has been given

the secret of the kingdom of God,

but for those outside, everything comes in parables” (Mark 4:11).

We like to think we’re included among the disciples—

that we’re there when Jesus is alone—

with whoever all’s there with his disciples,

but we overhear what two “explanations?”

Luke has some twenty-four parables,

Matthew twenty-three, Mark eight.

Some would say a few of John’s teachings are parables.

So we get a number of anywhere from 45 to 60 parables in the gospels.

And how many are interpreted? Explained?

Two.

And in Mark, just the one—the parable of the sower.

We are those outside more than we are those who know the secrets.

We get more stories than we do explanations.

We get more mystery than clarity.

What is it about a teacher

who wants students to wonder and ask questions

instead of have answers?

And why have we, as those students,

too much too often prioritized answers over questions?

What is it about a storyteller

who trusts the mystery

and who trusts the questions?

It’s something like someone who sows seed

and trusts the natural process of growth, isn’t it?—

who believes that something as little as a story

can shape a place, a way of being, a people—

can transform thinking and living

undermining Empire and all the narratives counter to God’s story,

and give people a home

in which to feel welcomed and beloved—

a home in which and from which

to sow and harvest and be nourished by

the good fruits of justice and kindness and and humility.

Can we expect that these days?

Justice and kindness and humility?

He does not speak to us except in parables

which take root in us … or not.

But if they do,

they grow and grow

and become magnificent … weeds

that are surprisingly … wonderfully …

big enough to welcome everyone … anyone.

Amidst all the shallow, ugly, mean stories of our days,

thanks be to God.