Scripture

Mark 6:1-13

He left that place and came to his home town, and his disciples followed him. On the sabbath he began to teach in the synagogue, and many who heard him were astounded. They said, ‘Where did this man get all this? What is this wisdom that has been given to him? What deeds of power are being done by his hands! Is not this the carpenter, the son of Mary and brother of James and Joses and Judas and Simon, and are not his sisters here with us?’ And they took offense at him. Then Jesus said to them, ‘Prophets are not without honor, except in their home town, and among their own kin, and in their own house.’ And he could do no deed of power there, except that he laid his hands on a few sick people and cured them. And he was amazed at their unbelief.

Then he went about among the villages teaching. He called the twelve and began to send them out two by two, and gave them authority over the unclean spirits. He ordered them to take nothing for their journey except a staff; no bread, no bag, no money in their belts; but to wear sandals and not to put on two tunics. He said to them, ‘Wherever you enter a house, stay there until you leave the place. If any place will not welcome you and they refuse to hear you, as you leave, shake off the dust that is on your feet as a testimony against them.’ So they went out and proclaimed that all should repent. They cast out many demons, and anointed with oil many who were sick and cured them.

You have heard the ancient story.

Let us listen now for the word of God.

Responsive Call to Worship (loosely based on Psalm 123)

To be Sung in Order to Get Back Up

From down here, I look up to You, God above.

That’s the image, isn’t it?

As day laborers look up to the boss who hired them,

as immigrants and refugees look up to the judge,

as the young black man looks up to the policeman,

as the woman looks up to the men making more than she does,

so our eyes look to You, O God, until we know divine mercy.

Have such mercy upon us, our God, have such mercy.

For we have had more than enough of the contempt.

Our souls overflow with the scorn of the arrogant—

with the sense of being looked down upon

by those we have to look up to.

Have mercy upon us, God above,

that we would know You here below. Mercy!

That we would know

You have deemed us worthy

of Your presence with us face to face.

Mercy!

Pastoral Prayer

Our God,

we are among those in one of Your communities of faith

who are taught to care for each other—

to take joy with those enjoying

and to weep with those in grief.

We are those taught to care for more

than just each other though—

commanded indeed, to love our neighbors and our enemies—

to provide for the least of these—

those without food and shelter and clothes—

those imprisoned.

We are those commanded to welcome the alien—

the refugee—

the ones who are different—

the ones who are left out.

We are those taught not to scapegoat—

to blame—

to crucify someone else for that

for which we are ourselves responsible.

We are those taught to be kind—

assured of love (both your love and the love of each other)

that we don’t need to tear down others

to feel good about ourselves—

don’t need constant attention

to be reassured of the value of our being.

We are those taught to be honest—

our yeses yeses, our no’s no’s.

That’s what Jesus said he expected of us.

We are those taught respect—

those who are to model grace.

We are those to whom you entrusted your creation.

We are to be good stewards

of the mountains and seas,

the air,

the plants and animals.

We are those through whom

you seek to bless all peoples.

So guide us ever into the wisdom of your way

grant us the courage to risk your way—

to trust your way

that we might be points of light in the darkness

that the darkness cannot comprehend

This we pray in the name of your way made flesh

our light in the darkness

still alive—present among us—

even Jesus the Christ,

amen.

Sermon

Jesus left that place, we read—Capernaum,

and came to his home town—Nazareth.

So begins one of my favorite Jesus stories.

On the sabbath, he began to teach in the synagogue

(as was his custom),

and many who heard him were astounded

(again, not unusual).

They said, “Where did this man get all this?

What is this wisdom that has been given to him?

What deeds of power are being done by his hands?”

Note the transition within their response

from “what is this wisdom?”

(that they were hearing for themselves)

to “what deeds of power are being done by his hands?”

(as the wisdom they heard firsthand

validated what they had heard

about Jesus’ deeds of power secondhand.)

So the first comment is about the wisdom they themselves heard.

The second comment is about deeds of power

they had heard about and were now prepared to accept.

“Is not this the carpenter, the son of Mary

and brother of James and Joses and Judas and Simon,

and are not his sisters here with us?”

And they took offense at him.

Again note,

it was not in disbelief that they turned on him—

taking offense at him.

It was rather, believing—

having heard the wisdom—

having accepted his power.

We, in our faith tradition and in our culture,

have prioritized believing over following.

But believing was never meant to be prioritized over following.

In fact, most of what we think believing connotes,

should be more associated with following.

Not only doesn’t it matter what we say we believe,

if we don’t follow,

it doesn’t matter what we actually do believe

if we don’t follow,

and if that’s true, then we have to entertain the possibility

that if you follow, it doesn’t matter what you believe.

Just think about it—

as the story asks us to.

Then Jesus said to them, “Prophets are not without honor,

except in their home town, and among their own kin,

and in their own house.”

Up until now in Mark’s gospel, Jesus has been identified

as the Son of God and the Holy One.

He has also acted in ways that identify him

as a proclaimer, a teacher, a healer, and a storyteller,

but here, for the first time, he self-identifies himself—

and self-identifies himself as a prophet,

which we know has nothing to do with foretelling some future,

and everything to do with speaking some truth.

And sometimes, most of us know this,

truth is hardest, maybe not to see, but to hear

from someone too close—

especially when it’s hard to hear—

(maybe when it’s been intentionally or customarily)

overlooked—even justified.

Who are you to point this out to us?

This that we don’t want to acknowledge.

We just got back from the beach,

and while out walking along the shore,

I noticed there were stretches of sand

where shells and shell shards seem to collect—

mounds of pieces of shells you wanted to walk around

if you were barefoot.

And usually, all those pieces merged into an indistinct mound,

but sometimes, amidst the indistinct, there would be a shape—

or a color, that stood out.

Two aspects of this gospel story stand out—

distinct—drawing attention.

Here’s the first:

And he could do no deed of power there.

That’s what it says.

Jesus could do no deeds of power.

Which warrants a quick refresher.

We’re five chapters into Mark’s gospel.

In those five chapters, Jesus has healed a man with an unclean spirit

in the synagogue in Capernaum on the sabbath (Mark 1: 21-28).

He healed many at Simon and Andrew’s house (Mark 1:29-34).

He went through Galilee proclaiming the message

and casting ut demons (Mark 1:39).

He healed a leper (Mark 1:40-42).

He healed a man paralyzed (Mark 2:3-12).

He healed the man with a withered hand

again on the sabbath (Mark 3:1-6).

He stilled a storm on the sea of Galilee (Mark 4:35-41).

He healed the Gerasene demoniac (Mark 5:1-20).

He raised Jairus’ daughter from the dead

and healed the woman with the flow of blood (Mark 5:21-43).

But in Nazareth, he could do no deeds of power.

Amidst all the expectations

and the celebration of who Jesus was and what all Jesus could do,

it says—the Bible says, Jesus could not do—

was unable to do—any miracles there.

For the Bible tells us so.

The first part of the story that stands out

was that Jesus could do no deeds of power there,

and the second is this:

except that he laid his hands on a few sick people—

and cured them!

He could do no deeds of power

except for the fact that he healed some people.

And he was amazed at their unbelief.

But it wasn’t unbelief, was it?

So what was it?

It was a lack of trust.

Most of what we associate with believing,

should be associated more with following.

And they wouldn’t follow him.

So he left.

Again, they didn’t follow.

Then he went about among the villages teaching.

He called the twelve and began to send them out two by two,

So, in the Bible, two by two …

makes you think of what?

The animals going onto the ark. Sure.

There’s even a song about it!

The animals entered the ark, two by two,

to preserve life through the flood.

Now the disciples go out, two by two,

to preserve the possibility of abundant life—

of life lived trusting grace—trusting love.

And Jesus gave them authority over the unclean spirits.

What does that mean?

It means if you trust love and grace,

you have authority over unclean spirits!

He ordered them to take nothing for their journey except a staff;

no bread, no bag, no money in their belts;

but to wear sandals and not to put on two tunics.

He ordered them to rely on others, in other words—

to not be independent and self-sufficient.

In our world, to be irresponsible.

Right?

He said to them, “Wherever you enter a house,

stay there until you leave the place.”

Now that’s called being mindfully present!

Don’t leave until you leave.

Be where you are.

We regularly interrupt the girls’ screen time

to tell them something like that.

“Hey! You’re here. Be here.

Here is unique and special, and you’re missing it.”

Too much of our experience (not just our youth and children’s)

has to do with not being present—

which is the opposite of every single wisdom tradition in the world.

Let me repeat that.

Our culture promotes and encourages not being present,

which is the opposite of every single wisdom tradition

in the history of the world.

“If any place will not welcome you and they refuse to hear you,

as you leave, shake off the dust that is on your feet

as a testimony against them.”

Don’t argue.

Don’t try and convince someone they need to listen to you.

Don’t overtalk them—

trying to exceed them in volume

as if that makes you more right

instead of more of an ignoramus.

We have so many ignorami in our culture—

and so many of them in the church.

So they went out and proclaimed that all should repent.

They cast out many demons,

and anointed with oil many who were sick

and cured them.

Ha!

We make of Jesus curing the sick—

healing lepers and making the blind to see—

making the one paralyzed able to walk—

casting out demons …

we make of that miracles.

And we make of miracles (of the miraculous),

the specialness of Jesus.

But the disciples did all that.

All those deeds of power

that in Nazareth,

we found out

weren’t deeds of power—

because he could do no deeds of power there,

except he did heal people.

Counter to the tradition of identifying holiness

by separating it from the ordinary,

we have been contemplating holiness as wholeness—

as not separating parts of reality from other parts—

parts of life from other parts.

Our gospel story questions separating Jesus from us

by virtue of what he did that we don’t understand and can’t do—

haven’t experienced.

Our gospel story questions making believing in miracles

the measure by which we follow Jesus

when trusting Jesus with our lives

seems a more reliable indication.

Actually living love and grace.

The ordinary choice to trust grace—

to risk love—day by day

is more the miracle —more the holy—

than any amazing thing we consider an act of power.

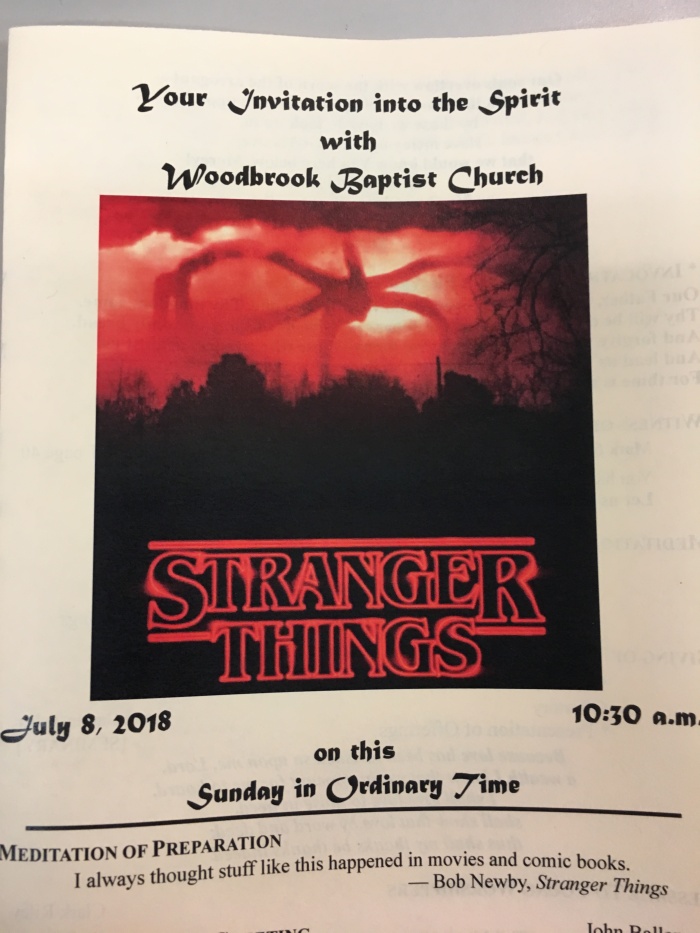

From considering the Netflix TV series, Stranger Things,

we know that El opened a gate between dimensions

that let the monster into our world.

And we know that once that gate was open,

the upside down (the monstrous dimension) grew or spread—

from the gate—from the basement of Hawkin’s Lab—

under the fields—through those weird tunnels.

We noted how the boys

were playing their game which was a campaign

that was part of a larger story of a quest.

We noted how that campaign—that quest

became their life—

a story that was true.

And there was the very real risk

of being consumed by the darkness—

such risk.

And what Will came to see is that everything in our reality

was also in the upside down.

There was an alternate version of everything.

That’s not to say that everything is good in our world

and only bad in the upside down,

but that in the upside down,

it was all is subject to the ravenous hunger of the monstrous.

And while everything in the right side up is not good,

it’s not subsumed into someone else’s—

something else’s—

wishes/hungers/lusts.

And in that world, as in ours,

in the upside down and the rightside up,

there is the light that overcomes the darkness—

the courage that confronts what’s dangerous—

the depth that acknowledges complexity—

the relationships that prompt action.

Here’s the thing.

If the upside down spreads and grows,

why wouldn’t the rightside up too?

There is the very real risk

in the world of Stranger Things—

in our world of stranger things,

of being consumed by the darkness—

that come from consuming darkness—

opening yourself up even just a little—

being mean—

graceless—

cruel.

Such risk.

And there is the very real possibility

in the world of Stranger Things—

in our world of stranger things,

of becoming a part of the light—

that comes from living light

opening yourself up even just a little—

being kind—

graceful—

thoughtful.

Such possibility.

There is the truth we proclaim

that mercy—

love—

grace—

kindness—

forgiveness—

joy—

wonder—

beauty …

they’re what transform reality—

transform people—

transform circumstances

by having transformed the people in the circumstances.

Not money.

Not power.

One of the books I read this past week

was by Laurie Frankel, called this is how it always is,

a beautiful book about a family in which the youngest son

grows up feeling like he’s really a girl—

and how her family loves her

through all the challenges that inevitably arise.

At the end of the novel, there was an author’s note that reads:

“[T[his book is an act of imagination,

an exercise in wish fulfillment,

because that is the other thing novelists do.

We imagine the world we hope for and endeavor,

with the greatest power we have, to bring that world into being.

[That’s what we do too, right? as followers of God]

I wish for my child, for all our children,

a world where they can be who they are and become their most loved,

blessed, appreciated selves. I’ve rewritten that sentence a dozen times,

and it never gets less cheesy,

I suppose because that’s the answer to the question.

THat’s what’s true. For my child, for all our children,

I want more options, more paths through the forest,

wider ranges of normal, and unconditional love.

Who doesn’t want that?

I know this book will be controversial, but honestly?

I keep forgetting why”

(Laurie Frankel, this is how it always is

[New York: Flatiron Books, 2017] 327).

More important than what you say you believe,

is whether you make the world a better place for children—

all children—

children separated from their parents—

children put in cages—

children used as threat—as deterrent—

as means to some end—any end—

children without adequate health care or food or education.

More important than what you say you believe—

more important than what you believe

is whether you work for more options—

whether you’re not threatened by wider ranges of normal—

whether you risk unconditional love

and the controversies

that make you forget why someone might think they are.

That’s following Jesus.

That’s trusting grace and risking love—

no matter what you do or don’t believe.