Scripture

Mark 3:19b-35

Then he went home, and the crowd came together again, so that they could not even eat. When his family heard it, they went out to restrain him, for people were saying, ‘He has gone out of his mind.’ And the scribes who came down from Jerusalem said, ‘He has Beelzebul, and by the ruler of the demons he casts out demons.’ And he called them to him, and spoke to them in parables, ‘How can Satan cast out Satan? If a kingdom is divided against itself, that kingdom cannot stand. And if a house is divided against itself, that house will not be able to stand. And if Satan has risen up against himself and is divided, he cannot stand, but his end has come. But no one can enter a strong man’s house and plunder his property without first tying up the strong man; then indeed the house can be plundered.

‘Truly I tell you, people will be forgiven for their sins and whatever blasphemies they utter; but whoever blasphemes against the Holy Spirit can never have forgiveness, but is guilty of an eternal sin’— for they had said, ‘He has an unclean spirit.’

Then his mother and his brothers came; and standing outside, they sent to him and called him. A crowd was sitting around him; and they said to him, ‘Your mother and your brothers and sisters* are outside, asking for you.’ And he replied, ‘Who are my mother and my brothers?’ And looking at those who sat around him, he said, ‘Here are my mother and my brothers! Whoever does the will of God is my brother and sister and mother.’

You have heard the ancient story.

Let us listen now for the word of God.

Responsive Call to Worship (loosely based on Psalm 130)

A Song of Getting Back Up

I’ve hit rock bottom,

and it’s You to whom I cry out.

Somewhat to my surprise,

honestly,

I don’t know if it’s in anger

or with something like maybe … hope.

Hear me, please.

I don’t know whether You hear me—

sometimes even whether You’re here to hear me,

but I do so want You to.

As manifestation of all that’s good and just,

I know I’ve fallen far short of Your hopes and expectations of me

and have no right to have hopes and expectations of You.

And yet part of what’s good about You,

if not just,

is Your grace—

Your forgiveness,

and so there’s hope.

So I sink into the stories of grace—

of undeserved forgiveness—

of unexpected welcome.

More than those who make it through the night

desperately waiting for the dawn,

my soul waits for You.

O creation, hope in God

for in the stories of God, there is ever the refrain of steadfast love

and the power and the will to redeem

even all who fall so far short.

Sermon

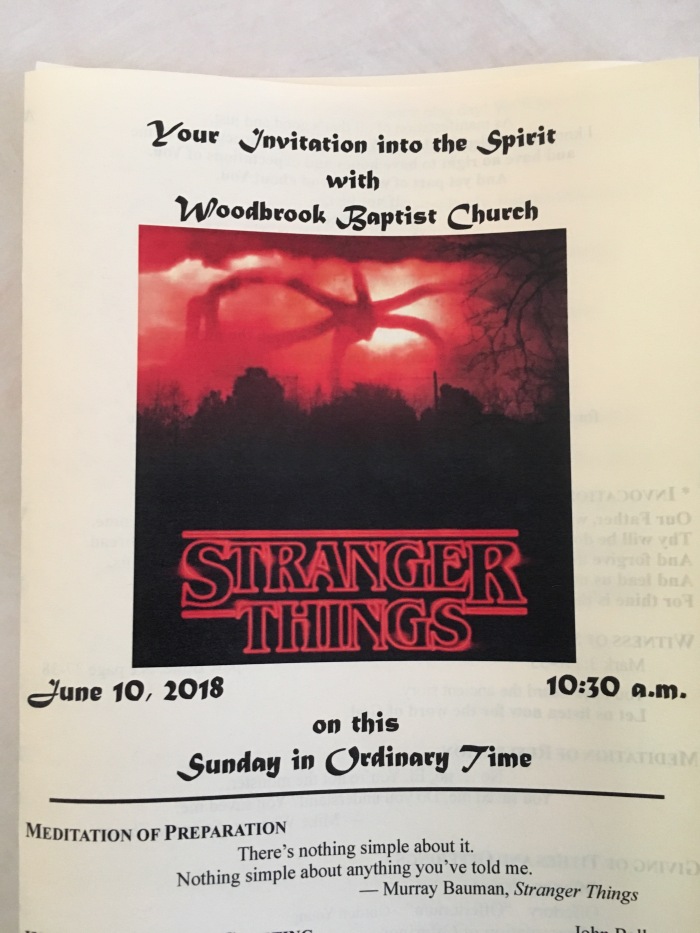

One of the beauties and joys of the Netflix TV series Stranger Things,

is its depiction of friendship and of family—

specifically the allegiances and commitments therein:

the allegiance and commitment a mom has to her child,

a brother has to his brother,

and friends have to a friend.

There’s such a powerful sense of interdependence

developed throughout the show—of mutual responsibility.

It’s an intimate bond that gradually extends

to a wider and wider group as the show progresses—

including—incorporating—more and more people into this

“I have your back,” “I’ll be there for you” intimacy.

Various combinations of characters

brave seriously creepy, scarily dangerous scenarios

that leave you thinking “I’m not sure I’d do that”

because someone matters to them.

And having faced the purity laws—the distinctions, divisions and judgments

of the religious establishment—having rejected the status quo

because people mattered to him more,

Jesus went home—

presumably back to Capernaum—

maybe to Simon and Andrew’s house (that’s where he’d been earlier).

And the crowd came together again (they’d been there earlier too) —

so many waiting to be healed—to be made whole,

and maybe wanting as well, to hear his good news—

stories of grace and forgiveness—of belonging and inclusion.

Why does religion so often need to be reminded

that it’s etymological root goes back to a Latin verb

meaning “to bind together”—not to divide, separate, or judge?

The crowd came together again, so that no one could even eat.

What does it mean to love others as you love yourself?

What does love mean when they’re desperate and you’re hungry?

When his family heard about this—got word of it,

they went out to restrain him.

The word means “to seize by force”—“to take control of!”

His family went out to restrain him.

It’s not that they didn’t like the crowds attracted to him.

It was more: “Get your priorities in order!

Take care of yourself. They’re not as important as you are.

How will you be able to keep helping people

if you don’t take care of yourself?

You’re going to burn out.”

They wanted to restrain him

for people (our translation reads) were saying,

“He has gone out of his mind.”

Most translations though, read that that’s what his family was saying

(“He’s off his rocker”), not people—

which makes sense.

Who else among the characters in our story would say that?

Not the crowd. They weren’t upset at what he was doing.

They wanted him to be doing more of it!

The disciples might have thought it,

but I don’t think they would have said it—yet.

No, this was his family—worried about him—

questioning his lack of boundaries.

“Come on, Jesus! Who doesn’t need time away from other people?

Who doesn’t limit their work time?

Who’s not selective in who they spend their mealtime with—

free time—leisure time? You are seriously off your gourd!”

I mean, doesn’t that sound like siblings?!

It’s the overstatement of those who care, but don’t understand.

“We’ve got your back, Jesus!

We’re here to take care of you!”

And there were scribes who came down from Jerusalem

“It is possible that they were official emissaries from the Great Sanhedrin

who came to examine Jesus’ miracles and to determine

whether Capernaum should be declared a ‘seduced city,’

the prey of an apostate preacher.

Such a declaration required a thorough investigation

made on the spot by official envoys,

in order to determine the extent of the defection

and to distinguish between the instigators, the apostates and the innocent”

(William L. Lane, The Gospel of Mark

[Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1974] 141).

How do you love others as yourself if you’re dividing them

into those included and those excluded?

How do you love others if you’ve taken it upon yourselves

to examine and investigate and name some innocent and some not?

And we have to be careful here,

because we all examine and investigate—and should,

but how do you love others if, in your investigating,

you’ve prioritized separation and exclusion over reconciliation?

These scribes said of Jesus,

“He has Beelzebul, and by the ruler of the demons he casts out demons.

We’re here to take care of him.”

It’s the oldest trick in the book.

If you have a dispute with someone in the public eye,

identify them first with and then as evil—

as someone from whom others need to be protected.

And he called them to him.

Now, by the rule of antecedents,

that means Jesus summoned the scribes.

He’s the immediate antecedent tot he pronoun “he;”

they’re the immediate antecedent to the pronoun “they.”

Which is weird—that they would have obeyed Jesus—

submitted to the very authority they were actively seeking

to question and undermine!

So either he had an undeniable authority even the scribes obeyed,

or they really thought they had him.

Or both!

Then, having summoned them, Jesus spoke to them in parables,

“The Greek word for parable … means literally a ‘setting beside’ …”

(Morna D. Hooker, The Gospel According to Saint Mark

[Peabody: Hendrickson, 1971] 116).

“So, on the one hand, you say

I cast out demons by the power of the prince of demons,

but on the other hand, how can Satan cast out Satan?

Demons play on the same team.

Satan doesn’t strike out Satan.

If demons started striking each other out,

the demonic team wouldn’t amount to much.

If a kingdom is divided against itself, that kingdom cannot stand.”

There are two associations here

that establish the logic of the progression in thought.

There’s the logical flow from the ruler of demons divided against himself

to the idea of the demonic kingdom as a divided kingdom.

But also within the historical context of the Jews,

Alexander’s Empire fell when it was divided between his generals.

The Jewish Hasmonean dynasty fell to Rome

leading to the loss of Jewish independence

when two brothers fought for the throne.

That particular sibling rivalry led to 12,000 Jews killed

in the final assault of Roman forces in Jerusalem

and General Pompey entering (and thus desecrating)

the Temple’s Holy of Holies.

Jesus goes on, “And if a house is divided against itself,

that house will not be able to stand.”

Now what’s the logical progression here?

I mean there’s the whole divided against itself motif,

but having gone from a ruler to a kingdom,

why go back to a house?

Unless this goes back to his house—

his family divided against him?

That makes some kind of sense.

But then it’s right back to Satan, with Jesus saying,

“And if Satan has risen up against himself and is divided,

he cannot stand, but his end has come.”

And it is true: evil can and does turn on itself.

But that doesn’t seem to be what our story’s about—

evil defeating itself.

So there’s consensus among scholars about this next verse:

“But no one can enter a strong man’s house

and plunder his property without first tying up the strong man;

then indeed the house can be plundered.”

Scholars agree that Satan, far from falling apart—

far from defeating himself—Satan is the strong man,

and Jesus, far from using Satan’s power.

defeats Satan’s powers and plunders his house—

hell, I guess—the demonic kingdom.

But—

a/ that doesn’t seem to be what our story’s about either.

I mean, if you strip the story down to its basics,

it’s about Jesus’ family and the scribes working against him—

undermining him.

Also, b/, don’t you think it’s kind of weird

to think of Jesus describing himself as a strong man

who binds someone else and plunders their house?

And finally, c/, as we think about a house being plundered,

we remember we’ve already encountered the image of a house—

one that will not be able to stand because it’s divided against itself,

and we wondered if that house might be Jesus’.

So if the strength of the house is unity,

and you bind that strength, you disrupt the unity.

And if this is Jesus’ house,

divisions within his family allow the house to be plundered.

And then, if you’re thinking institutionally as well,

divisions within the institutions of faith

threaten the stability and viability of those institutions.

So what if this isn’t about Jesus defeating the enemy,

but about the risk of Jesus being defeated—

the risk of Jesus’ house—the church being defeated—

not just by those against him—

actively, intentionally working to undermine him,

but also by those who care about him, but don’t understand him—

don’t understand his commitment to the world.

such that a rejection of Jesus

is the elevation of the comfortable self

over the whole.

“Truly I tell you, people will be forgiven for their sins

and whatever blasphemies they utter;

but whoever blasphemes against the Holy Spirit

can never have forgiveness, but is guilty of an eternal sin.”

I’m not so sure what to make of the idea of an unforgivable sin.

That seems to me to be something placing limits

on God’s love and God’s grace.

It also leaves us trying to identify what this particular sin is.

Because, well, if it’s unforgivable, I sure don’t want to do that one!

It tends to be ascribed to the scribes

who attributed to Satan the power Jesus manifest

and so, actually, thus committed themselves

the blasphemy of which they accused Jesus.

But given everyone who participates in divisive behavior

in our story, should we consider the possibility

that blasphemy might have something to do with caring about Jesus

and yet still undermining him and his mission—

something to do not with rejection, not with denial,

but with distortion in the name of affirmation?

Something to do with those who say, “We’ve got your back,”

but then stab you in the back

and justify racism,

are silent in the face of injustice,

who relegate women to a second class status,

who reject those created lgbtquia in God’s image,

who are mean,

whose yes is not a yes and whose no is not a no,

who justify both obscene wealth and obscene poverty—

and all in the name of Jesus.

Jesus might well just wisely reverse what Michael Corleone said,

and say “Keep your enemies close;

keep your friends closer!”

For they had said, we read, “He has an unclean spirit.”

Now who had said that?

We’re not sure, are we? It’s not a direct quote in our story.

So does it refer back to the scribes ascribing his power to a demon,

or to his family saying he was out of his mind?

Either way, note this is not a comment

made in response to what Jesus said about an unforgivable sin,

but it’s what prompted what Jesus said about an unforgivable sin.

Important to get the order right!

And it leaves me wondering if we waste time trying to identify some sin

when maybe Jesus was talking about an attitude.

Then his mother and his brothers came;

and standing outside, they sent to him and called him.

A crowd was sitting around him; and they said to him,

“Your mother and your brothers and sisters are outside, asking for you.”

The image here is of a house so packed full of people

that there are people surrounding the house who can’t get in.

Jesus’ family arrives and they’re stuck outside with all the others stuck outside.

Word is passed through the crowd,

“Hey, tell Jesus his family is out here!”

until it gets to those right around Jesus—until it gets to Jesus.

“Hey Jesus! Your family is out there.”

Now think about this.

The message had to have changed.

Not in the funny, garbled, distorted telephone game kind of way,

but from “He’s out here” to “He’s out there.”

Now I think it’s always important to affirm

that place and context change the content of what’s said.

But, more importantly,

we see there was division at the house in Capernaum—

not just between Jesus and his family, not just between Jesus and the scribes,

but also between those on the inside who could see and hear Jesus,

and those outside who wanted to see and hear him.

So I’m guessing, you had those on the inside,

“Your family, who has exclusive claims on you, is here,

and we’re afraid we’re out of luck.”

And maybe those outside, “His family is here,

maybe they will get him out here where we can see!”

But Jesus rejects exclusive claims and privileges.

“Who are my mother and my brothers?” he asks.

And looking at those who sat around him, he said,

“Here are my mother and my brothers!”—

which in the way we’re thinking about things,

sounds like it excludes the folks outside.

But Jesus goes on:

“Whoever does the will of God is my brother and sister and mother.”

“But John,” you might say,

“you’ve been talking about holiness as wholeness—

as not separating and dividing,

and here Jesus is separating.

He’s rejecting his family.

That’s monstrous!”

Except not really, right?

Jesus is separating himself from those who separate,

and he’s widening the definition of family to include anyone!

He’s rejecting an exclusive circle for an inclusive one—

rejecting a given blood tie, for a chosen tie,

Blessed be the tie that binds.

And for times such as ours, according to Jesus,

if the house is divided, you include others.

You include them.

You make it bigger!

You create a wider, less exclusive, more diverse community.

Y’all heard of Betty Bowers?

She’s the satirical persona of a Canadian comedian

who self-identifies as America’s Best Christian:

“I’m America’s Best Christian. God created me in His image

and I have MORE than returned the favor. Glory!”

Her pithy twitter comments are often quite searingly prophetic:

“Jesus forgave me for my sins so I could concentrate on yours.”

I cannot verify that all are appropriate, but the ones I’ve seen

are wickedly apropos.

She has also defined religious freedom, for example,

as “pretending to follow a religion you ignore

so you can be a [jerk] to people you hate, and then blame Jesus.”

That’s that attitude.

That’s the we’ve got your back; we stab you in the back thing.

That’s the risk Jesus faces in the world—

the church faces in the world.

It is so tricky.

Because it is so important not to be silent in the face of injustice—

in the face of sin.

It’s not about not saying anything about reprehensible behavior

towards women—towards blacks and latinos—

towards the lgbtquia community—

and calling it being nice—polite.

It’s not about not saying anything about reprehensible politics

that hurt vulnerable people

and saying worship is not the place for politics.

And, my friends, it needs to be said these days,

when it comes to the important responsibility of naming sin,

as followers of Jesus,

we should focus on what Jesus said, not what he didn’t.

And heaven forbid we should get all bent out of shape

about what he said nothing of

as we do not do what he explicitly said to do.

Because there goes integrity and relevance and a viable future.

Our faith is about taking responsibility for sin.

The systemic sins of our culture.

Other people’s sin, yes.

But always and only in the context of our own sin.

Confession first—

identification with another as sinner.

Identification not separation.

Wholeness.

Holiness even amidst sin.

May that comprise who we strive to be.